Digital twins - virtual replicas of existing built or natural heritage* - are not yet widely used by local authorities or the companies that manage or operate them. The first initiatives sometimes take very different forms depending on the context in which they are created: simulation tool, shared knowledge base, alerting "cockpit", etc. While we wait for organisations to build their own digital twins, one family of tools - which appeared in the early 2010s - prefigures them quite well: BIM collaboration platforms. They offer a highly effective way of sharing and exploiting the potential of digital models and are becoming a focal point for collaboration between engineering, construction and project management stakeholders. Only time will tell whether they have been the indispensable source of the emergence of digital twins... But what exactly are the ingredients of these platforms that should contribute to the success of digital twins? Here are a few pointers drawn from our engineers' daily experience of orchestrating these platforms on major projects.

Ergonomics: the sine qua non for platform adoption

If collaboration is to benefit as many people as possible in the long term, it must be as user-friendly and robust as possible. Far from being "engineers' tools for engineers", collaboration platforms are aimed not so much at BIM or GIS specialists, but at all engineering professionals. In the case of digital twins, this will be all the more true for those involved in management, operation/maintenance, emergency services (firefighters, police), etc.

What should ergonomics take into account? First and foremost, access: in order to quickly and easily bring all players on board these virtual representations of reality, it is preferable to use web platforms rather than software that has to be installed "hard" on the user's computer. Our teams and customers can attest to this: web technologies have improved considerably in recent years, allowing us to eliminate the constraints of updates, operating system compatibility, etc., while offering a powerful graphical interface that can be accessed through a traditional browser. In addition, Single Sign On (SSO) simplifies the experience for users who connect to the platforms with their corporate ID.

Ergonomics also means smooth navigation. There are many graphics engines, and most are now based on streaming technologies (the display is progressive, depending on the level of detail required), but few can satisfactorily handle complex building models, tens of kilometres of infrastructure or vast territories.

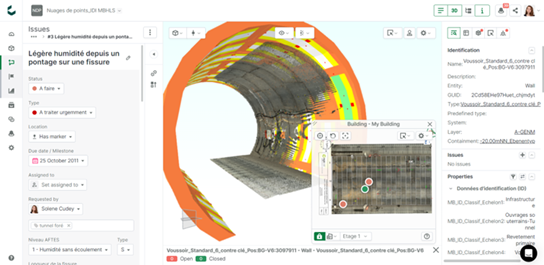

Finally, the intuitive nature of the functionalities essential for collaboration contributes to the overall ergonomics of these platforms: searching and filtering elements, "teleporting" to a given location in a virtual representation, measuring distances or surfaces, customising colours and displays, etc., all without the need for lengthy training campaigns. Collaboration also means being able to communicate through the models. We have seen this in the 6 years that Egis has been implementing platforms for major construction projects using BIM: it is the ability to use them as a tool for dialogue between project stakeholders that allows us to offer our clients the added value of BIM and to develop solutions that are acceptable to the various stakeholders (see our video on the stakeholders' testimonial for the Lyon Metro B project). Today, these "geolocalised technical discussion management" functions can be used to manage lists of unresolved issues or requests for changes during the design or construction phase (almost 5,000 technical issues were studied for the Lyon metro B extension project). It's only a matter of time before operation and maintenance professionals benefit from it, for example in managing technical incidents or diagnosing their installations. They could also use it to report on the latest developments in the field more quickly, if necessary, and thus help to make the twins more reliable.

Bringing together different types of data: an essential feature of digital twins

One of the main values of twins is to provide a systemic view of a structure or area. The collaborative platforms at the heart of digital twins must therefore be able to read and assemble - we also say "federate" - the various technical layers of these models: the general architecture, the technical electronic systems, the ventilation, but also the definition of the various technical zones, the materialisation of regulatory constraints linked to flows, minimum safety distances, etc. They must therefore not be limited to the design of the building, but also to the design of the building itself.

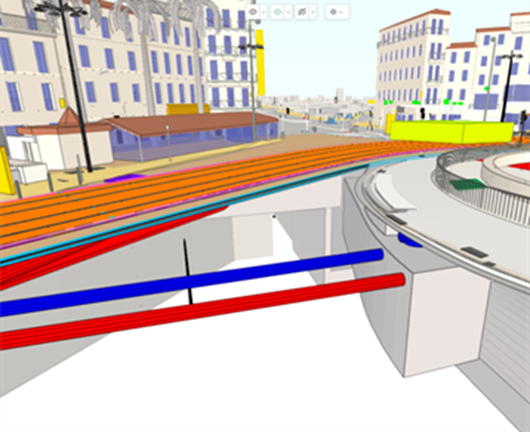

They cannot be limited to BIM models or GIS maps, but must include both. And why? Because it is the cross-referencing of local (BIM) and global (GIS) data that enables more informed decisions to be made. For example, on the 6 km extension of the Marseille tramway, the combination of 2D and 3D allowed us to define with greater certainty the routing of the underground network systems, a prerequisite for the construction of the tramway.

Extract from the Marseille tramway extension project, modelled in BIM

Another source of data to consider is point clouds. Point clouds have become accessible and are a first step in the process of digitising our heritage, as undertaken in the Digital Twins projects. They are a valuable source of information for users, allowing them to remotely project themselves into a building or infrastructure, take measurements... and build on an experience now widely democratised by Google Street Maps. By integrating point clouds into their maintenance planning activities, managers can better understand the current condition of structures and more easily identify the context and constraints (access, safety, interface with users, etc.), as was the case in the experiment carried out with the operators of the M25 motorway ring around London.

As promising as they are, point clouds have their limitations. Unlike BIM models or GIS maps, 3D scenes derived from point clouds are poorly structured and difficult to extract, filter and interrogate, unless they have been manually enriched with keywords... In addition, only the parts visible to the Lidar (Laser Imaging Detection and Ranging) scanner at the time of acquisition are rendered: areas covered by vehicles and buried components such as reinforcements, underground networks, etc. are missing from the cloud. A final factor that is not neutral at a time when the environmental footprint of digital technology is a growing concern: point clouds are very heavy in terms of the volume of data that needs to be hosted and backed up, with a ratio of 100x compared to a BIM model. Expanding and storing them would have an environmental impact that would defeat their purpose. So we need to find a balance and a healthy way of using these "clouds" - which are clouds in name only!

Example of the federation of BIM models and point clouds, extracted from a tunnel, using Catenda Hub

Example of a point cloud linked to maintenance data from a CMMS, for Brisbane's InnerCityBypass, using Sensat

Use open formats: making software building blocks interoperate

The digital platforms at the heart of digital twins must not only be designed for a wide range of users, but must also be able to integrate seamlessly into a wider and constantly evolving technological ecosystem. Internet of Things (IoT) hubs, command and control interfaces (SCADA), maintenance management support tools (CMMS), field data collection applications, etc. are all solutions currently in use by asset managers or operators, with which it is important to connect. They also need to feed into more advanced decision making, forecasting and simulation modules, both in the past and in the future, as well as being connected to immersive visitation systems or automatic video-based fault detection systems (computer vision). For this reason, these platforms must have a portal for accessing the information they hold, known in IT jargon as an API (application programming interface).

These platforms must also read and transmit their information natively using open information exchange protocols (IFC, BCF, CityGML, Geopackage, Osm and GeoJSON, etc.).

Why is this a must for asset managers? For three reasons:

- Durability: in the long term, open formats are maintained by industry consortia such as Building Smart International, ensuring that asset data can be read 50 years from now, even if the software used to create it has disappeared or is no longer backward compatible.

- Transparency: for decision makers, open formats guarantee data transparency and unfiltered use of their content.

- Competition: the use of open formats stimulates competition and puts both small and large digital companies on a level playing field when it comes to developing new services and software based on legacy data. It also ensures that customers are not locked into the ecosystem of a single software vendor.

Enabling co-creation: for truly useful functionality

To date, there is no ideal collaboration platform, each with its own strengths and limitations. Like more and more players in the engineering, construction and operation sectors, Egis has turned to digital players, and in this case has chosen to work with one of them, Catenda, on a collaboration model based on co-construction.

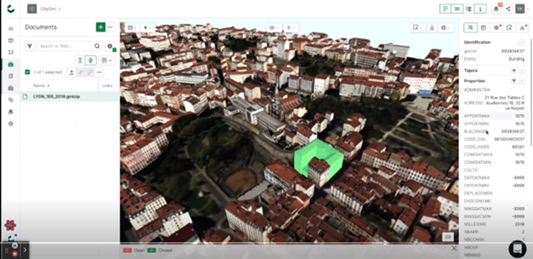

After 5 years of using the Catenda Hub (formerly Bimsync) platform for the BIM models of its major projects, Egis has decided to work on the definition of new functionalities to be developed on Catenda Hub in 2022. The name of this programme is "LYKT". LYKT" means "lantern" in Norwegian, the large lantern at the head of a locomotive. Starting with an initial list of orientations (use of linear infrastructure data in the latest IFC 4.3 format, easier search for information in models, faster integration of geomatic information and territorial models around a model of a structure, etc.), Egis mobilised a team of engineers who gradually designed each of these functionalities. In regular workshops, the Egis and Catenda teams coordinate and discuss the proposals made by the development teams, taking into account the technical constraints of the architectures, which are not always visible to the "average person", and validating the directions taken. A few weeks later, at the end of each development sprint, the engineers test the results, which are then immediately available to the projects.

Integration of CityGML models into the Catenda Hub platform (Lykt project)

This agile process, far removed from the traditional customer-supplier relationship, will reach its final destination at the end of 2024. In itself, it testifies to the rapprochement that is taking place between the IT professions (developers) and the engineering professions, in favour of tools that are better adapted to the challenges of eco-design and enable the value of collective intelligence to be realised!